Indicator 9: Cesarean section as a proportion of all expected births

The population cesarean section rate is the proportion of expected live births that were delivered via cesarean section.1

Numerator:No. women who had cesarean sections in facilities

Denominator:Expected live births

× 100Purpose

The rate of cesarean section in a population is among the most often cited indicators of underuse and of over-medicalization of care. The population-based cesarean section rate (CSR) is an indicator that informs us about access to and utilization of life-saving care for both woman and baby; it also helps identify inequities in the distribution and delivery of this care and can raise questions about the appropriateness of care.2 Extremes at either end of the use spectrum carry risks of adverse consequences for both women and newborns, thus, the importance of monitoring rates and trends to identify the underuse and overuse of cesarean sections.3

Data collection and calculation

The numerator is the number of women who had cesarean sections registered in all facilities (both government and private sector facilities). This includes both emergency and elective or programmed cesarean sections regardless of medical indication (both maternal and fetal). The primary source for the numerator is a facility’s operating theatre register or logbook. The number of women who had cesarean sections in government health facilities is often found in routine HMIS systems. The number of women who had cesarean sections in private sector facilities may need to be collected from other sources (although ideally, private sector facilities should also report service statistics to the national HMIS). In many countries the private sector contributes substantially to the population CSR, so it is important to include those facilities when calculating the indicator.

The denominator is an estimate of all the live births expected in a specified geographical area, based on the crude birth rate. It is calculated by multiplying the total population of a selected area by the most recent estimate of the crude birth rate of the same area, and dividing by 1,000. In countries with strong civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems, the actual number of births can be used in place of the estimation derived from the crude birth rate.

Unlike the institutional CSR (which measures the proportion of births in facilities that were delivered via cesarean section), the denominator of this indicator is at the population level.

Common alternative sources for calculating the population CSR are population-based surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys which rely on women’s self-report of having had a cesarean section (see footnote at the top of this page).

The indicator is typically expressed as a percentage (per 100 expected births).

Analysis and interpretation

The benchmark for this indicator is set at 10%.6

Very low rates of cesarean section (far below 10%) signal an unmet need for cesarean section, poor access to surgical care, and are associated with elevated maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.7 Low population CSRs raise the possibility of: low utilization of the health system, perhaps driven by distrust or financial and socio-cultural barriers; a poorly functioning referral system and other access barriers; or systemic problems related to facility readiness to perform a cesarean section such as a shortage of health professionals with surgical and anesthetist skills, or shortages in equipment and supplies.

Very high rates (substantially over 10%) suggest overuse or over-medicalization, non-medically indicated care, and potential financial burdens for health systems, individual women and families. High population CSRs could be indicative of: issues with provider practices, clinical decision-making, and the quality of care; a shortage of skilled health personnel who are competent and equipped to perform assisted vaginal delivery (e.g., use vacuum extraction when clinically indicated); inappropriate care, as the result of policies such as those that restrict ambulation during the first stage of labor89 or financially incentivize CS, require routine use of cesarean section in cases of stillbirth, do not require consent for cesarean section, and restrict the use of VBAC (“once a cesarean, always a cesarean”).

The national population CSR can mask sub-national differences, where certain areas may be farther from reaching national targets, and extremes of underutilization and over-medicalization may co-occur. Stratifying the population CSR for sub-national areas can be useful, as long as a trustworthy denominator exists. This requires disaggregating the numerator and denominator by the relevant sub-area.

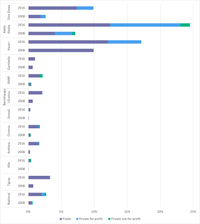

The population CSR can also be disaggregated by facility characteristics to provide more information about where cesarean sections are being performed. This is done by disaggregating the numerator by managing authority (public vs. private sector; see Figure 1), by facility level (tertiary hospitals vs. district hospitals), by EmONC classification, or by elements of readiness (e.g., tracer commodities readiness scores and adequate human resources).

Figure 1: Contribution of managing authority to population CSRs, by region (Ethiopia, 2016)

Source: Beyene MG, Zemedu TG, Gebregiorgis AH, Ruano AL, Bailey PE. Cesarean delivery rates, hospital readiness and quality of clinical management in Ethiopia: national results from two cross-sectional emergency obstetric and newborn care assessments. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2021; 21:571.

It is not recommended to calculate this indicator for a single facility or a small administrative unit. It is challenging to estimate the denominator (expected number of births in the catchment area) when calculated at such a local level, and the numerator can also be distorted by women receiving services at cesarean-capable facilities in neighboring catchment areas.

Supplemental studies

The population CSR is simply a rate and tells us little about equity, medical indication, accountability, clinical quality, or safety of the procedure. If stratification by urban/rural or users’ characteristics (e.g., women’s socio-economic status) is desired, such analyses are more easily done using population-based survey data. However, health facility assessments can collect data about some user characteristics and about clinical quality through cesarean section audits or chart reviews, or other special modules designed for that purpose. [AMDD EmONC assessment: module 8]

Managers may want to track how many cesarean sections are done at individual facilities (using the number of women who gave birth at the facility as the denominator). However, the institutional cesarean section rate can be difficult to interpret as it is influenced by factors beyond clinically indicated need such as a facility’s medical complexity, whether it is a teaching hospital, its proximity to other surgical facilities, institutional provider practice, organizational culture, financial incentives as well as socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the women delivering at the facility. Therefore, alongside the institutional cesarean section rate, it can be useful to conduct cesarean section audits or chart reviews, conduct studies on post-surgical infection if it is determined that that is a problem10 and use the Robson classification to better understand cesarean section practices at individual facilities (please see below). It may also be useful in these special studies to segregate cesarean sections performed during the day (8 am – 8 pm) and night (8 pm-8 am). When the majority of cesarean sections are performed during the day and few cesarean sections are performed at night, that may indicate inadequate 24h/7d EmONC readiness.

Using the Robson Classification System to assess cesarean sections

The Robson classification has become the global standard for assessing, monitoring and comparing institutional cesarean section rates within facilities over time and between facilities. It is a tool to measure prospectively the cesarean section rate for 10 mutually exclusive groups of women, defined by 6 basic obstetric characteristics (parity, previous cesarean section, onset of labor, gestational age, number of fetuses, and fetal lie and presentation).11 WHO’s Robson Classification: Implementation Manual (2017) lays out how to implement and interpret the classification system.12

According to the Implementation Manual, the Robson classification system helps facilities to accomplish several things:

- identify and analyze the groups of women who contribute most and least to overall institutional cesarean section rates;

- compare practice in these groups of women with other facilities that have more desirable results in order to consider changes in practice;

- assess the effectiveness of strategies or interventions targeted at optimizing the use of cesarean section;

- assess the quality of care and of clinical management practices by analyzing outcomes by groups of women; and

- assess the quality of the data collected and raise staff awareness about the importance of these data, interpretation and use.13

Multiple agencies and initiatives promote indicators based on the Robson classification. The WHO Standards for Improving the Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities recommends “the proportion of Group 114 women who receive a cesarean section” as a quality outcome and process measure to track over time.15 ENAP/EPMM have also listed this indicator in their Roadmap (version January 2023), while the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecoclogy (ACOG) focuses on Groups 1-416 because of their impact on the overall CSR (and the increasing relative size of Group 5).1718

Women and providers’ perspectives on cesarean sections

When cesarean section rates are high, planners and managers may want to interview health providers and women to learn what they think contributes to those results. Providers could be asked about their training, opinion and confidence to perform assisted vaginal births in place of performing cesarean sections. They could also be asked how they make decisions about when to do cesarean sections, and what role women’s requests for cesarean sections plays in their provision of care. For example, a study in Bangladesh found that some providers believe that the high rate of cesarean section is in part due to a growing number of women who ask to have cesarean sections because they believe they are safer for their babies and because they ‘fear labor pain.’19 At the same time, women could also be interviewed to find out their opinions about cesarean sections versus normal vaginal births and what information they receive from health providers about modes of childbirth. Based on these types of interviews, evidence-based health education campaigns could be designed to separately target health providers and women to promote good-quality childbirth practices and to address any misinformation/misperceptions.

Note that this indicator differs slightly from the household survey-derived cesarean section indicator. This indicator counts all cesarean sections in the numerator, whereas household surveys (e.g., Demographic Health Surveys, Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys) define the numerator as number of live births delivered by cesarean section (disaggregated to those that had a planned cesarean section before the onset of labor pains, and those for whom the decision for a cesarean section was made after the onset of labor pains). The denominator for this indicator is the expected number of live births within a specified time period, whereas household surveys define the denominator as number of live births in the last 3-5 years. The reason for these differences is that the EmONC Framework recommends analyzing the population CSR annually, which is more feasibly achieved by using facility data for the numerator and estimating the denominator than by conducting household surveys annually. ↩︎

Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, Comande D, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2176-92. 4:Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(6). ↩︎

Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(6). ↩︎

Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Souza JP, Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(6). ↩︎

World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme. WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod Health Matters. 2015;23(45):149-50. ↩︎

World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme. WHO

Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod Health Matters.

2015;23(45):149-50. ↩︎Sobhy S, Arroyo-Manzano D, Murugesu N, Karthikeyan G, Kumar V,

Kaur I, et al. Maternal and perinatal mortality and complications

associated with caesarean section in low-income and middle-income

countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet.

2019;393(10184):1973-82. ↩︎Alhafez L, Berghella V. Evidence-based labor management: first

stage of labor (part 3). Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM.

2020;2(4):100185. ↩︎Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, Styles C. Maternal positions

and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2013(10):CD003934. ↩︎Bagheri Nejad S, Allegranzi B, Syed SB, Ellis B, Pittet D. Health-care-associated infection in Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:757–765. ↩︎

World Health Organization. Robson Classification: Implementation Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Report No.: 978-92-4-151319-7 ↩︎

World Health Organization. Robson Classification: Implementation Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Report No.: 978-92-4-151319-7 ↩︎

World Health Organization. Robson Classification: Implementation Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Report No.: 978-92-4-151319-7 ↩︎

Group 1: Nulliparous women with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks gestation in spontaneous labor. ↩︎

World Health Organization. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2016. ↩︎

Group 2: Nulliparous women with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks gestation who either had labor induced or the CS was performed before onset of labor. Groups 3 and 4 mirror Groups 1 and 2 except they include multiparous women. ↩︎

Group 5: All multiparous women with at least one previous CS, with a single cephalic pregnancy, ≥37 weeks gestation. ↩︎

D'Agostini Marin DF, da Rosa Wernke A, Dannehl D, de Araujo D, Koch GF, Marcal Zanoni K, et al. The Project Appropriate Birth and a reduction in caesarean section rates: an analysis using the Robson classification system. BJOG. 2021. ↩︎

Chowdhury, Mahbub Elahi; Khan, Rasheda; Soltana, Nahian; Alam, Falguni; Jahan, Shamin Ara: Afsana, Kaosar. Re-Visioning Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC) Framework: Bangladesh Case Study Final Report. Dhaka, Bangladesh: 2023. ↩︎