Background and context

This is the third edition of the UN guide for planning and monitoring emergency obstetric care. The first set of indicators to do high-level monitoring of emergency care for women with complications during childbirth was published in 1997, at a time when the vast majority of women gave birth at home and both the evidence base and the experience base for efforts to strengthen emergency obstetric care at scale, were fairly thin.1 In 2009, the emergency obstetric care framework and guide were updated based, in large part, on experience of the previous 10 years in implementing programmes to strengthen emergency obstetric care in Africa, Asia and Latin America.2

Changes in the maternal and newborn health landscape

Since 2009, there have been important changes in the maternal newborn health landscape. In many countries around the world, institutional delivery has massively increased, driven by better physical access to facilities, government incentives, and cultural change.34 But even large increases in institutional delivery have not always resulted in declines in maternal mortality.5 This has led to the recognition that the quality of the care received in facilities is often extremely poor and that quality improvement is essential for reducing maternal and newborn deaths.6

In the quality improvement field, trends from human rights, health systems strengthening and implementation science have come together to create new norms. Quality of care can no longer be seen as simply a supply side issue of improving technical delivery of clinical interventions in the facility. Macro-level drivers of poor quality, such as discrimination, must also be addressed. Moreover, it is now well-accepted that quality of care must include both the provision of care and the experience of care, brought together in a health system that is fundamentally people-centered.7

When care is people-centered, services are organized and conducted in ways that incorporate the perspective of those who use them. In childbirth, perhaps nothing is as important to women as the survival of their newborns and nothing is as important for newborn wellbeing as the survival and well-being of their mothers. The global maternal and newborn health communities, which operated quite separately for decades, are now seeking to better integrate their efforts. One result has been an increased focus on keeping the mother-newborn dyad together as much as possible during their stay in a facility, even in the event of obstetric or newborn complications.

Building on experiences from EmONC implementation

The Guide also builds on lessons learned from a strong body of experience using the previous indicator set and implementing and monitoring EmONC. Since 1997, dozens of countries have conducted national EmONC assessments (see Figure 1). UNFPA has developed implementation strategies and guidance for designating and monitoring EmONC networks, starting with countries in Francophone West Africa.8 Initiatives such as the 13-year project in Kigoma, Tanzania have creatively re-designed services to bring EmONC within reach for millions of people.910 Some countries have also invested significantly in expanding inpatient care for small and sick newborns,11 bringing increasing recognition that alignment of facility-based newborn services with obstetric services will streamline planning and monitoring.

Figure 1: Countries that have completed EmONC assessments (1997-2022)

The Re-Visioning EmONC process and evidence base for revised EmONC Framework describes a number of the learnings that have come from this work on EmONC, but here we highlight three insights that relate specifically to planning:

-

Complications are unpredictable - Complications often happen unexpectedly, in women and newborns with no known risk factors. Although we estimate that EmONC services will be needed for 15 – 30% of any population (see Estimating need for emergency obstetric care), we do not know which individuals those will be. Some individual patients can, of course, be identified as high-risk and should be managed accordingly. And many complications can now be prevented through good quality antenatal and routine intrapartum care, such as active management of third stage of labor to prevent post-partum hemorrhage. Yet, many complications still happen in women and newborns with no known risk factors. The system therefore cannot rely solely on risk stratification to target EmONC in advance. It must be ready to meet the needs of its entire population on an emergency basis.

-

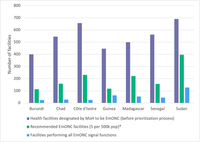

Strategic prioritization is essential - EmONC facilities require certain conditions to work effectively and efficiently. They manage emergency situations where time is of the essence. EmONC facilities must be close enough to where people live that they can reach care quickly, 24 hours a day, seven days a week (24h/7d). The distance between lower- and higher-level facilities must be short enough to make timely referral possible. At first thought, the answer to the time urgency challenge might seem to be to establish EmONC facilities everywhere. But an EmONC facility must manage a large enough volume of women and newborns with complications for providers to keep up their skills and for the health workforce, drugs and equipment to be used and maintained efficiently. Consequently, it is possible to have too many facilities attempting to provide EmONC resulting in too few able to provide quality EmONC 24h/7d. If governments simply decide, for example, that all health centers should provide Basic EmONC services, then in most cases, resources, including the most critical human resources, will be spread too thin, and performance will not match designation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Facilities designated vs. recommended vs. performing EmONC

Source: Unpublished paper by UNFPA.

Years for designated & recommended figures: Burundi-2017, Chad-2019, Côte d’Ivoire-2019, Guinea-2017, Madagascar-2019, Senegal-2018, Sudan-2018.

Years for performing figures: Burundi-2019, Chad-2018, Côte d’Ivoire-2017, Guinea-2017, Madagascar-2017, Senegal-2016, Sudan-2017

* Based on recommendations from 2009 EmONC Framework

-

Planning must happen on short, medium, and long-term timeframes – To make planning an even more challenging process, we know that, by definition, long, multi-year time frames must be projected for training and deploying new cadres of the specific skilled health professionals needed for EmONC. Often such plans must be carried out under fluctuating resource constraints and ever-present political considerations. Thus planning must happen on multiple time horizons simultaneously. Immediate, short-term steps, even bold short-term steps, can always be taken to achieve some mortality reduction quickly and equitably. Indeed, the imperative of human rights requires that such steps must be taken.12 But for big impact, to move from one stage of the perinatal transition to another, countries must simultaneously create and act on a bigger vision of their future.

The EmONC Framework and the guidance provided here on how to use the Framework assume that long-term planning is largely done via strategic plans on approximately a 10-year time horizon. Medium-term planning is typically done via programme planning cycles of 3-5 years. And short-term planning is done on an annual basis. Of course, these time frames should be modified to fit the specific planning timeline used in each country.

Despite the strategies and programming that have been put into place over the last two decades and the overall global reduction in annual maternal and newborn deaths since 1997, in many places, maternal and newborn mortality remain stubbornly high, especially among poor, vulnerable and marginalized populations. Even when assessments reveal profound problems, the changes that ensue are too often just nibbles at the edges. Investment remains shaky. Ambitions stated on paper fail to translate into meaningful change. Negligible programs, programs that do too little to disrupt a dysfunctional system, border on forsaking the women and newborns who have been asked to rely on its services.1314

A new vision of EmONC, a new approach to assessment and its integration into existing planning processes, and a new level of ambition are needed to truly change the terrible toll that maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity take on communities around the globe.

Aligning with other global initiatives

In the decades since the EmONC Framework was first developed, there has been a proliferation of global initiatives on maternal and newborn health, many of which include their own monitoring frameworks. Recognizing the ever-increasing burden of data collection on health care workers and district managers, wherever possible, the EmONC Framework links directly to other initiatives, aligning indicators and data collection tools and processes. Below we touch on a few key initiatives and explain how the EmONC Framework aligns with or differs from them. Most importantly, unlike some other MNH tools and initiatives, the EmONC Framework is not intended for global reporting or global accountability purposes. It is meant to support countries in generating data and analyses for their own planning and monitoring purposes.

Chief among the aligned initiatives is Every Woman Every Newborn Everywhere (EWENE, formerly ENAP/EPMM), the UN-led initiative supporting countries to develop acceleration plans to meet global maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirth reduction goals. EWENE has created a short facility assessment tool (the LAT: Light Assessment Tool) to gather facility data on a yearly basis. Many of the indicators in the revised EmONC Framework can be measured using routine health facility data and data gathered through the LAT.

Thinking about the EmONC system and its users dynamically – changing over time in response to many internal and external conditions – links usefully to the MNH transition model and to the policy and programme tools that build on it.15161718 While it is possible to look retrospectively and identify stages that countries have gone through from high to low mortality, experience in the implementation of service delivery teaches that there is no single model that can be imposed from outside onto a complex system to accelerate its move through these transition stages.19 No service delivery system can jump overnight to an imagined aspirational future without engaging in its own social, cultural, and political processes to get there.202122 Investment and technical support from outside can hasten a country’s progress. Ultimately, however, the people who will solve the problems are the people who actually experience the problems on the ground and understand their dynamics best. (See The Re-Visioning EmONC process and evidence base for revised EmONC Framework for a summary of findings from a series of country studies.23) Tools like the EmONC Framework help to make the problem legible, to quantify its dimensions and highlight its context.

The perspective of this Guide aligns with the ambition of service delivery redesign initiatives,2425 called for in multiple commissions and working groups,26 and now funded in multiple countries through the World Bank as well as by UNFPA in 15 countries.2728 Some of these initiatives have prioritized maternal and newborn health with a strong focus on access to EmONC. The EmONC Framework may be a useful tool to support this process since it starts with asking countries to consider their ambitions in a 10-year time frame, and then to see where they are, assess their present performance, and then dig deep to understand how a major reimagining of their health system can lead to meaningful change.

UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA. 1997. Guidelines for Monitoring the Availability and Use of Obstetric Services. UNICEF: New York, NY. ↩︎

WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, AMDD (2009). Monitoring emergency obstetric care: A handbook. WHO:Geneva. ↩︎

Montagu, D., Sudhinaraset, M., Diamond-Smith, N., Campbell, O., Gabrysch, S., Freedman, L., Kruk, M. E., & Donnay, F. (2017). Where women go to deliver: understanding the changing landscape of childbirth in Africa and Asia. Health policy and planning, 32(8), 1146–1152. ↩︎

Goudar, S.S., Goco, N., Somannavar, M.S. et al. Institutional deliveries and stillbirth and neonatal mortality in the Global Network's Maternal and Newborn Health Registry. Reprod Health 17 (Suppl 3), 179 (2020). ↩︎

Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. India's Conditional Cash Transfer Programme (the JSY) to Promote Institutional Birth: Is There an Association between Institutional Birth Proportion and Maternal Mortality?. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67452. Published 2013 Jun 27. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067452 ↩︎

Kruk, M. E., Gage, A. D., Arsenault, C., Jordan, K., Leslie, H. H., Roder-DeWan, S., Adeyi, O., Barker, P., Daelmans, B., Doubova, S. V., English, M., García-Elorrio, E., Guanais, F., Gureje, O., Hirschhorn, L. R., Jiang, L., Kelley, E., Lemango, E. T., Liljestrand, J., Malata, A., … Pate, M. (2018). High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. The Lancet. Global health, 6(11), e1196–e1252. ↩︎

Tunçalp, Ӧ., Were, W. M., MacLennan, C., Oladapo, O. T., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Bahl, R., Daelmans, B., Mathai, M., Say, L., Kristensen, F., Temmerman, M., & Bustreo, F. (2015). Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns-the WHO vision. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 122(8), 1045–1049. ↩︎

Brun M, Monet JP, Moreira I, Agbigbi Y, Lysias J, Schaaf M, Ray N. Implementation manual for developing a national network of maternity units - Improving Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (EmONC), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), 2020. ↩︎

Prasad, N., Mwakatundu, N., Dominico, S., Masako, P., Mongo, W., Mwanshemele, Y., Maro, G., Subi, L., Chaote, P., Rusibamayila, N., Ruiz, A., Schmidt, K., Kasanga, M. G., Lobis, S., & Serbanescu, F. (2022). Improving Maternal and Reproductive Health in Kigoma, Tanzania: A 13-Year Initiative. Global health, science and practice, 10(2), e2100484. ↩︎

Dominico, S., Serbanescu, F., Mwakatundu, N., Kasanga, M. G., Chaote, P., Subi, L., Maro, G., Prasad, N., Ruiz, A., Mongo, W., Schmidt, K., & Lobis, S. (2022). A Comprehensive Approach to Improving Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care in Kigoma, Tanzania. Global health, science and practice, 10(2), e2100485. ↩︎

WHO-UNICEF Expert and Country Consultation on Small and/or Sick Newborn Care Group (2023). A comprehensive model for scaling up care for small and/or sick newborns at district level-based on country experiences presented at a WHO-UNICEF expert consultation. Journal of global health, 13, 03023. ↩︎

Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. (2014) Human rights-based approach to reduce preventable maternal morbidity and mortality: Technical Guidance. ↩︎

Pasha O et al. (2013) A combined community- and facility-based approach to improve pregnancy outcomes in low-resource settings: a Global Network cluster randomized trial. BMC Med. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-215. ↩︎

Hawe P (2015) Minimal, negligible and negligent interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 138:265-268. ↩︎

Souza, J. P., Tunçalp, Ö., Vogel, J. P., Bohren, M., Widmer, M., Oladapo, O. T., Say, L., Gülmezoglu, A. M., & Temmerman, M. (2014). Obstetric transition: the pathway towards ending preventable maternal deaths. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 121 Suppl 1, 1–4. ↩︎

Souza, J. P., Day, L. T., Rezende-Gomes, A. C., Zhang, J., Mori, R., Baguiya, A., Jayaratne, K., Osoti, A., Vogel, J. P., Campbell, O., Mugerwa, K. Y., Lumbiganon, P., Tunçalp, Ö., Cresswell, J., Say, L., Moran, A. C., & Oladapo, O. T. (2024). A global analysis of the determinants of maternal health and transitions in maternal mortality. The Lancet. Global health, 12(2), e306–e316. ↩︎

Boerma, T., Campbell, O. M. R., Amouzou, A., Blumenberg, C., Blencowe, H., Moran, A., Lawn, J. E., & Ikilezi, G. (2023). Maternal mortality, stillbirths, and neonatal mortality: a transition model based on analyses of 151 countries. The Lancet. Global health, 11(7), e1024–e1031. ↩︎

Forthcoming. ↩︎

Campbell, O. M. R., Amouzou, A., Blumenberg, C., Boerma, T., & Countdown to 2030 Exemplars Collaboration (2024). Learning from success: the main drivers of the maternal and newborn health transition in seven positive-outlier countries and implications for future policies and programmes. BMJ global health, 9(Suppl 2), e012126. ↩︎

Freedman L. (2011). Integrating HIV and Maternal Health Services: Will Organizational Culture Clash Sow the Seeds of a New and Improved Implementation Practice? JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 57: p S80-82. DOI: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821dba2d ↩︎

Percival V et al. (2023). The Lancet Commission on peaceful societies through health equity and gender equality. Lancet. Sep 4:S0140-6736(23)01348-X. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01348-X. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37689077. ↩︎

Pritchett L and Woolcock M (2004). Solutions When the Solution is the Problem: Arraying the Disarray in Development. World Development. 12(2): 191-212. ↩︎

Forthcoming. ↩︎

Roder-DeWan, S., Madhavan, S., Subramanian, S., Nimako, K., Lashari, T., Bathula, A. N., Sathurappan, R., Kumar, S., & Chopra, M. (2023). Service delivery redesign is a process, not a model of care. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 380, e071651. ↩︎

Roder-DeWan S, Nimako K, Twum-Danso NAY, Amatya A, Langer A, Kruk M. Health system redesign for maternal and newborn survival: rethinking care models to close the global equity gap. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002539. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002539 - DOI - PMC – PubMed. ↩︎

Kruk, M. E., Gage, A. D., Arsenault, C., Jordan, K., Leslie, H. H., Roder-DeWan, S., Adeyi, O., Barker, P., Daelmans, B., Doubova, S. V., English, M., García-Elorrio, E., Guanais, F., Gureje, O., Hirschhorn, L. R., Jiang, L., Kelley, E., Lemango, E. T., Liljestrand, J., Malata, A., … Pate, M. (2018). High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. The Lancet. Global health, 6(11), e1196–e1252. ↩︎

Global Financing Facility. Building high quality health systems: Service delivery redesign for maternal and newborn health. [Webinar.] ↩︎

UNFPA. Catalyzing action amidst global challenges – The Maternal and Newborn Health Thematic Fund 2022 annual report. New York, NY: UNFPA, 2023. ↩︎